This year, the celebration of the reunification of the Primorska region to the Slovenian homeland takes place in Nova Gorica on September 15th. That same day marks the celebration of the 70th anniversary of the start of construction of the new city (Nova Gorica) along the border. There is no way to deny or even to diminish the horrors suffered by the Slovenian people on the Italian side of the border after the implementation of the Treaty of Rapallo in 1920 which annexed the Primorska region to Italy. After the rise of Italian fascism two years later, however, the suffering only escalated for Slovenes. The Slovene language was prohibited in public and every minor violation was severely punished by the Carabinieri with torture, and even deaths of Slovenes in Italian dungeons were recorded as a result of simple infractions of the ban on speaking Slovene in their territory.

Towards the end of World War 2 the reign of fascist terror ended, and the Primorska region located in the disputed territory between Italy and Yugoslavia was consequently returned to the then-emerging new Slavic state.

How Tito gained and lost Trieste, Gorizia and Friuli-Venezia Giulia region

The first division of the coastal territory took place at the Versailles Peace Conference at the end of World War 1, where the victors redrew the map and delineated the new Europe.

Although the United States was never formally involved in the later alliance of the Allied forces, due to their participation in the war the Americans took part in the peace conference. Because of its shift of allegiance during the war, Italy had its own territorial demands which included the Primorska region. The Americans tried to counter their demands with the proposed Wilson Line which established the border between the Kingdoms of Italy and Yugoslavia along a vertical line above Rijeka so that the Kindom of Yugoslavia would include Idrija, Postojna, with Senožeče becoming a border town along with Podgrad in Ilirska Bistrica. Yugoslavia later managed to negotiate the border with the Treaty of Rapallo, which pushed Italian territory deep into Slovenian national territory. As a result, with the rise of fascism two years later, many more Slovenians experienced fascist terror than would have been the case had Wilson’s line been adopted at the peace conference.

Twenty years later, a new war slaughter of global proportions began and Italy placed its bets on the wrong side and in 1943 ended up on the losing side. The surrender of Italy to the Allies was signed by Walter Bedell Smith and Giuseppe Castellano at Cassibile in Sicily, and in it Italy renounced Friuli-Venezia Giulia as part of the surrender. This territory was later occupied by the Allies advancing to the north.

Negotiations between Tito and Field Marshal Alexander over the western border of Yugoslavia with Italy started to take place even during World War 2, first in July 1944 and later in Belgrade in February 1945. At the last meeting, Field Marshal Alexander emphasized the need for allied access to Trieste for the purpose of supplying their troops advancing through Austria toward Germany. Tito agreed to the administration of Friuli-Venezia Giulia by the Allied military authority as negotiated by Field Marshal Alexander at the 1944 meeting, provided the Allies recognize the previously established communist administrative services in the region. Field Marshal Alexander agreed and assured Tito that the Allies’ military authority would not jeopardize Yugoslav territorial demands in the peace negotiations. Members of the Alliance wanted to hold off on the establishment of new border decisions until peace negotiations at the conclusion of the European conflict and the signing of Germany’s surrender.

Despite the Allies’ promises, Tito was convinced by Foreign Minister Josip Smodlaka not to trust foreign promises, regardless of which side they came from and to rely solely on the military capabilities of the Yugoslav Partisans. In the following months, in spite of Tito’s promises to the Allies, there were indications that Yugoslavia wanted to annex the Friuli-Venezia Giulia region even before the peace negotiations.

On April 26th, shortly after the Partisans entered Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Borba, the official Yugoslav communist newspaper, announced the annexation of the region to Yugoslavia by local communist rulers upon the capitulation of Italy and that claim to the region was confirmed in AVNOJ (the Anti-fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia) and “that the entry of the Partisan army in the area assured that the recently annexed territory of Friuli-Venezia Giulia would also remain Yugoslavian.”

On May 1st Tito announced that the Partisans had reached the Soča River on the Italian side and occupied Trieste and Gorizia. Only a day later, the British announced that their New Zealand units occupied those same cities. Due to the contradictory British statement, the Partisan Command announced that the entry of Allies into Trieste and Gorizia “without their permission will have dire consequences.” The local Partisan leadership accused the British of breaking a deal between Tito and Alexander and demanded the establishment of a communist authority in the area. Tito even requested the British withdraw to the west side of the Soča River, thereby clearly violating the agreement he had made with Field Marshal Alexander.

In order to avoid further misunderstandings regarding the agreement, Field Marshal Alexander sent his Chief of Staff, General Lieutenant Colonel Morgan, to Tito on May 8th to submit a written version of his verbal agreements during the meetings of 1944 and 1945 with Tito. By signing the agreement, Tito would secure the new border between Italy and Yugoslavia at the mouth of the Soča River by which Gorizia, Trieste and Monfalcone would become part of Yugoslavia according to the peace negotiations. In return for the promised territory, the Americans demanded only that Partisan units withdraw from the region. By not signing the agreement, Tito dismissed General Lieutenant Colonel Morgan with the words “The situation has changed, the problem is no longer military, but rather political.” He denied the withdrawal of Partisan units from the area. Along with his refusal, he demanded the installation of communist rulers in administrative positions in the occupied territory of Friuli-Venezia Giulia and promised new territorial demands west of Soča river at the peace negotiations.

In the ensuing days, events intensified as the Partisans failed to capture Klagenfurt along with other unsuccessful military actions which proved the Partisans’ military tactics inferior to those of the British and American forces. The Allies’ aim was to establish an Allied military authority in the region ahead of the peace negotiations which would divide up territory among countries. Field Marshal Alexander wrote on May 19th in a message to his units that he was trying to strike a compromise with Tito peacefully, without success. He emphasized that the Allies did not oppose Yugoslav territorial demands for Friuli-Venezia Giulia, but that Tito was trying to exert control over the region militarily. Field Marshal Alexander concluded his message by saying “Actions that all too closely resemble Hitler, Mussolini and Japan.’

Tito attempted unilateral military campaigns in the region and opposed the Allies in order to increase his support among the Yugoslav people, especially the anti-Partisan Serbs, and tried to capture Stalin’s attention by proving his socialist orientation in the conduct of foreign policy towards Western allies. Moreover, these were not the last actions by Tito which infuriated the Americans and, as a result, Trieste as well as Gorizia and the border with Italy at the mouth of the Soča River were taken from Yugoslavian hands.

Yugoslavia’s departure from the West after the war

After the end of the war, Tito was hoping to occupy two chairs: ideologically in connection with the Soviet Union and yet with the expectation of Allied assistance while simultaneously trying to establish his authority in Yugoslav territory. In this, the communist leaders in Ljubljana faithfully helped him with their lies, yet all this led later to the final surrender of Trieste, Gorizia and the Friuli-Venezia Giulia region to Italy when the border zones were done away with.

The beginning of the final disputes between the Americans and Yugoslavia can be found in the Nationalization Law, which was enacted at the end of 1946, and which threatened the Americans with the loss of German companies seized during the war in Yugoslav territory. The disputes then continued with an incident involving the disappearance in Occupied Zone A to Yugoslavia on July 12th of eight British soldiers and seven German prisoners of war and then an attack by Yugoslav military units on U.S. military personnel in the occupied zone on the 13th. The boiling point was reached in August 1946 with Yugoslav attacks on U.S. airplanes over Slovenian airspace.

The Americans used regular flight routes between Vienna, Venice and Rome during post-war operations. Sometimes due to weather conditions over Brenner Pass and at other times in order to shorten flight distances, their transport aircraft flew at times over Yugoslav airspace on the direct Vienna-Italy line. At that time, Tito was already looking for new allies due to economic developments involving nationalizations, based on ideology, looking especially to the Soviet dictator Stalin. He demonstrated his hatred for the West by prohibiting aerial crossings of Yugoslav airspace by the Allied powers and going as far as bringing down Allied aircraft.

The first incident over Slovenian airspace took place on August 8th 1946 when Yugoslav air forces based in Ljubljana forced a U.S. C-47 transport plane to crash land in a field near Kranj. One of the U.S. crew members was badly wounded by machine gun fire during the incident, and the others were detained by Yugoslavia at a hotel in Ljubljana, which the Americans repeatedly diplomatically protested in demand of their release. The next incident happened on August 19th 1946 when Yugoslav air forces from Ljubljana brought down another C-47 transport plane, killing all five crew members. In a statement on August 21st, Tito refuted the statements made by the U.S. Ambassador to Yugoslavia, Patterson, who said that the plane had gone astray due to weather conditions. Tito claimed to have observed clear skies on August 19th at his Brdo pri Kranju summer residence. On the basis of data he received from the command of the Yugoslav Air Force in Ljubljana, Tito stated that from July 16th until August 8th Yugoslav airspace had been violated by 172 aircraft, mostly bombers. According to him, this constituted a direct attack by the Americans on the new communist regime. American commanders from both Austria and Italy, however, confirmed only 74 aircraft along this line, mostly transport planes.

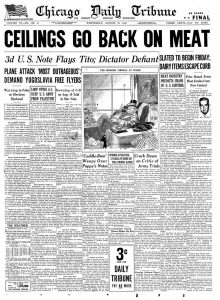

A number of U.S. and British newspapers reported on these incidents, with the Chicago Daily Tribune even dedicating three pages to this news in their August 21st issue. Yugoslavia denied U.S. officials access to the crash sites in both cases. The U.S. and European public were bitterly angry at the events in Yugoslavia and at Marshal Tito’s arrogance regarding the execution of the U.S. flight crew by taking down the transport plane. Public opinion turned against Yugoslavia and the proposal to locate the border along the south Soča River to its mouth at the Adriatic Sea faded from the maps.

Americans expected respect for the wartime agreement between Tito and the Field Marshal to allocate new territory to a young land, an allocation which did not later occur, due to Tito’s attempts to capture Stalin’s attention and his statement that “Yugoslavia is a peaceful country, but not at all costs.”

The above reasons for the loss of Trieste, Gorizia and the border along the south Soča River are revealed in U.S. intelligence documents declassified by the CIA in 2002. These documents testify to the arrogance of the dictator Tito during the post-war period and his inexperience on the international military political scene.

OSS documents revealing truth behind loss of Trieste and Gorizia for Yugoslavia

Tito, preferring to score political points within his nation, personally let slip from his hands Trieste, the most important port in the north Adriatic Sea, as well as Gorizia, for which Yugoslav communist authorities would later compensate by constructing Nova Gorica. It is a city which is still reminded by an inscription in stone on Sabotin reading “TITO” that Yugoslavia and now Slovenia could have retained the city of Gorizia on the other side of the border. Yet Slovenians are still paying for his arrogance even today, because the country is now divided over the construction of a second railroad track to the most important Slovenian port in Koper, for without Tito and his incompetence that port could be Trieste, which has already built a two-track railway all the way to Sežana. Unfortunately, because of the incompetence of the Yugoslav communist authorities and that of Marshal Tito, this route from Sežana runs through the Italian side of the border all the way to the Italian port of Trieste.

Sebastjan J